The Sphere

The sphere is a symbol of the Self, of Unity, in that every one of its faces is but one, and all points on the circumference are at the same distance from the centre.

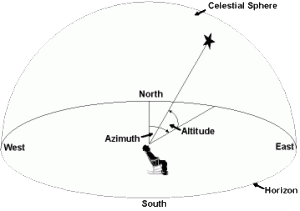

It stands for wholeness, whether material or spiritual, expressing the totality of the Being in all its aspects; it denotes enlightenment and human perfection, and it suggests non-differentiation, thus is a symbol of the divine, of infinity and eternity, and of sacred time — the notime of enlightenment stretched out into infinite dimensions. The base of the cube stillness is the point that gives rise to a motion which, when circular, embodies the basis for the spiral, the helix, and is the rhythm of the original sine wave. It is the ring, the wheel, the Ouroboros, or the taijitu — the structure and dynamics of the cosmos in the metaphysical sense comprising yin & yang — or the sun-wheel, the sun disk, gold, solidified light, immortality. For Plato, it symbolizes the psyche; Empedocles figures God as a rounded sphairo enjoying a circular solitude; St. Bonaventure and Nicholas of Cusa maintain that “God is an intelligible sphere whose centre is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” For a long time, the sky was conceived as a hemisphere covering the earth.

When the sphere is distorted, it becomes an ovoid, an oval, the Cosmic Egg, the Primordial Fireball, or the white hole Big Banging in producing the physical universe complementary to the spiritual realm.

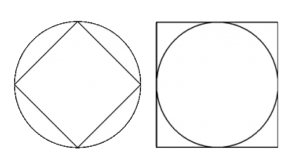

For the Chinese, the symbol of Heaven is a circle, while that of Earth is a square.

Humans have always striven to combine the square and the circle. The simplest such combination is a square inscribed in a circle or a circle inscribed in a square, which is the basic form of the mandala of both the Amerindians’ sand paintings and of the Hindu and Buddhist related iconography for the map of consciousness; in Chinese symbolic cosmology the golden mandala is a squared circle, akin to the Hermetic and alchemists concept of “squaring the circle”, the is to say, the descent of spirit into matter, or the divine into the human, a completion that Jung identifies in the individuation process, far from the mundane aspiration to transmute physical lead into physical gold, rather the goal of shaping up the “glorious body” — the Christian resurrection body, or the Buddhist diamond body — hence, it is the true Gold of which the physical version is a manifestation on the mundane plane.

Old alchemical drawings depict a square nested in a circle, with a small circle at the centre, out of which radiate, along the diagonals of the square, four lines dividing the figure into four sections corresponding to the four classical elementals air, water, fire, earth — also the four directions of space, the four functions of the psyche, etc. — while the circle in the middle is the quintessence, the fifth element. In Cave 3.0, this paradigm is reflected in the floor structural composition of the Venue.

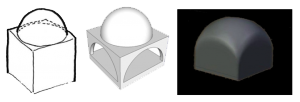

The Hemisphere – The Dome

A dome (Lat. domus) is a rounded vault made of either curved segments or, as in Euclidean assessment, by a surface of revolution, a space created by rotating a curve around its central vertical, the Axis mundi in Cave 3.0.

A dome is an architectural element resembling the hollow upper half of a sphere; it can rest upon a rotunda, or drum, or tholobates, e.g., a cylindrical or polygonal wall with or without windows. A tambour, or lantern, is the equivalent structure over a dome’s oculus supporting a ‘cupola’, another word for ‘dome’ usually used for a small dome upon a roof, and at times used to describe the inner side of a dome.

As with arches, the ‘springing’ of a dome is the level from which the dome rises. In Cave 3.0, this level is taken up by the Mesoteric stage on the Cube. The top of a dome is the ‘crown’ — the cabalistic kether — through which keystone[1] goes the Axis mundi. The inner side of a dome is the ‘intrados’, the outer, the ‘extrados’; the part of an arch halfway between the base and the top is the ‘haunch’[2].

The upper portion of a masonry dome is always in compression and is supported laterally — so it does not collapse except as a whole unit — and a range of deviations from the ideal in this shallow upper cap is equally stable[3].

When the base of the dome does not match the plan of the supporting walls beneath it, techniques are employed to bridge the two, the simplest of which is to use diagonal lintels across the corners of the walls to create an octagonal base[4].

Because domes are concave from below, they can reflect sound and create echoes. A dome may have a ‘whispering gallery’ at its base that, at certain places, transmits distinct sound to other distant places in the gallery[5].

Geodesic domes are the upper portion of geodesic spheres. They are composed of a framework of triangles in a polyhedron pattern. Such domes can be created using a limited number of simple elements and joints and efficiently resolve domes internal forces[6].

In antiquity, dome-shaped tombs were used as a reproduction of the God-given shelter made permanent as a venerated home of the dead and were widespread mortuary traditions — as in the Indian stupas, the Iberian tholos, or the Sardinian muraghe. They were associated with the heavens in Ancient Persia and in the Hellenistic-Roman world[7].

The dual sepulchral and heavenly symbolism was adopted by early Christians in both the use of domes in architecture and in the ciborium, a conical canopy like the baldachin used as a ritual covering for relics or the church altar; the chuppah (Heb. חוּפָּה), under which a Jewish couple stands during their wedding ceremony. In the early centuries of Islam, domes were closely associated with royalty in its metaphysical bearing. A dome built in front of the mihrab of a mosque was initially meant to emphasise the place of the male energy during royal ceremonies. Over time, such domes became primarily focal points for decoration or the direction (qibla) of prayer.

[1] A keystone, or capstone, is the wedge-shaped stone piece at the apex of a masonry arch, or the generally round one at the apex of a vault. It is the final piece placed in construction to lock all the stones into position, thus allowing the arch/vault, to bear weight. Although a masonry arch/vault cannot be self-supporting until the keystone is placed, the keystone experiences the least stress of any of the voussoirs due to its position at the apex.

A related symbology stemming from the Axis mundi is the meaning of the imperial parasol common to diverse cultures, in which the canopy stands for Heaven’s vault, supported and sectioned by a numerological assigned value of 8 or more ribs/pillars mounted on a pole, the Axis mundi uniting Heaven to Earth. Another symbolical analogy is cased in the bow-arch and the arrow binomial, in which the archer stands for the acting agent, the actor.

In a rib-vaulted ceiling, keystones may mark the intersections of two or more arched ribs. Architects of the 16th century often designed arches with enlarged and slightly dropped keystones, numerous examples of which are found in the work of Sebastiano Serlio, the 16th-century Italian Renaissance architect and theoretician author of the Architettura (eight books, 1537–75), the first Renaissance work on architecture to devote a section to the theatre. His many treatises included illustrations of the tragic, comic and satyric stages, based on Vitruvius’s innovative ideas regarding the vanishing point. Serlio’s sets are constructed in function of this point, at which parallel lines are drawn in perspective converge. He was also the first to employ the term “scenography,” and to make extensive use of the scenic space and lighting to give the impression of depth. With his technical innovations, Serlio had a profound impact on the theatrical architecture of his age, on theatrical scene design and stage lighting. An early manuscript of his Architettura is preserved in the Avery Architectural Library, Columbia.

[2] A masonry dome produces thrusts down and outward at right angles from one another. Meridional forces —like the lines of longitude on a globe — are compressive and increase towards the base; hoop forces — like the lines of latitude on a globe — are in compression at the top and in tension at the base, with the transition in a hemispherical dome occurring at an angle of 51.8 degrees from the top. The thrusts generated by a dome are directly proportional to the weight of its materials.

[3] Because voussoir domes have lateral support, they can be made much thinner than corresponding arches of the same span. The optimal shape for a masonry dome of equal thickness is a revolved catenary curve, similar to the curve of a parabola. This shape provides for perfect compression, with none of the tension or bending forces that masonry is weak against. The pointed profiles of Gothic domes approximate this optimal shape than do hemispheres, favoured by Roman and Byzantine architects due to the circle being considered the most perfect of forms. Adding a weight to the top of the pointed dome, such as in the Brunelleschi cupola at the top of Florence Cathedral, changes the optimal shape to perfectly match the actual pointed shape of the dome.

The outward thrusts in the lower portion of a hemispherical masonry dome can be counteracted with the use of chains incorporated around the circumference or with external buttressing, although cracking along the meridians is natural. For small or tall domes with less horizontal thrust, the thickness of the supporting arches or walls can be enough to resist deformation, which is why drums tend to be much thicker than the domes they support.

[4] Another technique uses arches to span the corners, which can support more weight. A variety of these use squinches — single arch or a set of multiple projecting nested arches placed diagonally over an internal corner, and which can take a variety of other forms. Another technique uses pendentives, triangular sections of a sphere with a diameter equal to the diagonal of the square bay. Domes with pendentives can be divided into simple and compound: in the former, the pendentives are part of the same sphere as the dome itself; in the latter, they are part of the surface of a larger sphere below that of the dome itself and form a circular base for either the dome or a drum section.

[5] The half-domes over the apses of Byzantine churches helped to project the chants of the clergy. Although this can complement the music, it may make speech less intelligible, leading Francesco Giorgi (1535) to recommend vaulted ceilings for the choir areas of a church, but a flat ceiling filled with as many coffers as possible for where preaching would occur. Cavities in the form of jars built into the inner surface of a dome may serve to compensate for this interference by diffusing sound in all directions, eliminating echoes while creating a “divine effect” in the atmosphere of worship. This technique was written about by Vitruvius in his Ten Books on Architecture which describes bronze and earthenware resonators. The material, shape, contents, and placement of these cavity resonators reinforce certain frequencies or absorbs them.

[6] Although not first invented by Richard Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983), geodesic domes are associated with him because he designed many and patented them in the United States.

[7] The distinct symbolism of the heavenly or cosmic tent stemming from the royal audience tents of Achaemenid and Indian rulers was adopted by Roman rulers in imitation of Alexander the Great, becoming thus the imperial baldachin.